“Know Thyself” — Ancient Delphic maxim

“Knowledge is Power” — Inscription on the New York Psychoanalytic Institute. Often attributed to Francis Bacon, it is more accurately credited to Thomas Hobbes.

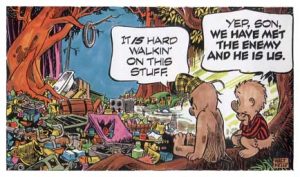

“We have met the enemy and he is us!” — Cartoonist Walt Kelley

Psychology is a young science, having gained entrance to the academy only in the latter half of the nineteenth century. Before that it was regarded as a branch of philosophy; natural philosophy, as all sciences were known back at the start of The Enlightenment. Back then, psychology was not a thing! In the 18th and 19th centuries, the physical sciences emerged first, then the biological sciences, and finally, the social sciences took their present form in the late 19th and in the twentieth century. This post builds on themes first articulated herehttps://elephantinthehottub.com/2015/08/everything-you-know-is-wrong

Psychology’s first out professional was William Wundt, a German physician who was the first to label himself a ‘psychologist’ and set up a research lab. He is properly regarded as the founding father of experimental psychology. Back in 1885, as Freud and Breuer were publishing Studies in Hysteria, and Von Krafft-Ebing was releasing the first edition of Psychopathia Sexualis, and Alfred Binet was opining about associations and fetishism, it is possible to imagine that there was something in the water. The sudden change in the zeitgeist was leading to the emergence of new academic disciplines. The social sciences were getting formed in the image of the physical sciences that brought steam power, railroads, instantaneous communication through the telephone, telegraph and radio, electric light, and soon, relativistic notions that would upset the old social order and the very definition of reality.

This new science was getting energized by concepts like free association, the techniques of introspection, participant observation, and unlike the abstract concepts of electrons, ether, and radio waves, the exciting corpus of discovery was ourselves. There was no need for fancy equipment, William James taught that we could start right in closely observing and introspecting about ourselves. One of Freud’s greatest works would prominently discuss his own dreams.

Unreliability of Observations:

But the exciting new science of psychology was almost killed in its crib when the boundless successes of the physical sciences crashed up against a very serious problem. Hugo Munsterburg, Wundt’s first research assistant, started to look at ways in which the emerging science of psychology might influence the legal profession. Having trained in Wundt’s lab to carefully observe psychophysiological activity, he noticed that even very smart people who could be expected to be paying close attention did not give identical accounts of social events. In a famous demonstration, he arranged for two actors to stage a carefully scripted assault upon one another in the amphitheater and challenged his medical students to describe what they had seen. When the written accounts of the event were collected, Munsterburg reported that the physical descriptions of the men ranged broadly, and observers could not agree upon the start or outcome of the altercation. Some reported a weapon where none was present. Others misattributed dialogue, and lines were made up that were nowhere in the script. Munsterburg went on to challenge the legal profession to accept this and other evidence of the unreliability of eyewitness testimony, but he got nowhere near changing anything. For his trouble, he did found forensic psychology as a profession, which was much needed at the time as the world of criminology was seized by the plague of phrenology, the pseudoscience of diagnosing the propensity for criminal behavior by the shapes and patterns of bumps on one’s head. Lacking rudimentary statistics and a cohesive theory about how to apply them, overgeneralizations and misattributions of causality were hard to restrain. After all, if humans had indeed descended from apes as Darwin had suggested, then perhaps humans with ape-like skulls were socially retrograde. These dangerous free associations went on to inspire bad criminology and eugenics theories that were seized by the later Nazis.

But Munsterburg’s work also raised serious questions about what good a science of human psychology might be if it couldn’t trust any of its observations. One of the great enduring themes in psychology has been the problematical limitations of our conventional wisdom about ourselves and what psychological experimentation and theory suggest about us. Munsterburg emigrated to the US during this early period of development, helping to establish the Harvard psychology program, but remained an ardent Germanophile. He is little remembered today outside of forensic psychology having been somewhat sidelined by his open advocacy for Germany just as the US became embroiled in World War I over the aggressive German policy of unrestricted submarine warfare. Munsterburg died in December of 1916, 5 months before the US entry into the war which doomed the Central Powers. Chances are good this is the first you have heard of him!

The Dynamic Unconscious:

Not the first, but perhaps the greatest of all the contestants taking a whack at the pinata of our self-concepts was Sigmund Freud. Completely unrepentant about his assault, he eschewed the very use of the term ‘self’ itself. He coined the terms ‘id,’ ‘ego,’ and ‘superego’ to precisely convey Freud’s idea that we had no unitary self at all. Rather what passed for our mental process was an amalgam of independent agencies with conflicting purposes, the compromises among them reflected constant internal conflicts. Our mundane notions of goals, purposes and self were all defenses to soothe our discomforts about reconciling our animal impulses with our lofty social rules and expectations.

Freud’s vision was particularly dark because most of our thoughts are unconscious, and therefore lost to us accept through laborious psychoanalysis. And because the constant conflict between our sexual and aggressive desires and our social demands was both painful and unceasing, even in psychoanalysis, humans could never completely know themselves or escape this conflict. Alone on a desert island with no others to govern us, we still carried the legacies of our early experiences in society and our internalizations of what was right and wrong. For Freud, a crucial part of ourselves was not just unknown, but unknowable. Freud was not the first to observe that we did not know all our own thoughts. Associationists like Binet and neurologists like Charcot had recognized unconscious associations long before Freud. The unconscious was easily demonstrated with hypnotism, which was much studied at the time. But Freud was first to explain that the unconscious was a product of internal conflict.

Classical Conditioning:

Matters were not greatly improved when the great Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov won the 1904 Nobel Prize in Medicine for his exploration of dog’s digestive physiology using the technique of classical conditioning. This discovery launched the field of behaviorism. By demonstrating that we could learn things absent volitional control or intention, Pavlov undermined our notions of agency and personal responsibility. Both Freud and Pavlov raised the specter of mechanistic determinism the libertines had gone to great lengths to dispel. But behaviorism and psychoanalysis would vie for the imagination of later psychologists and undergird huge advances in psychological research.

The Problem of Personality Traits and Behavior:

The tension between psychoanalysis and behaviorism was very much at the heart of Gordon Allport’s invention of trait theory, which attempted to create an alternative basis for personality theory that was neither behavioral nor psychodynamic. Allport disliked Freudian theory’s recourse to explaining present day adult adjustment to early childhood experiences but objected to behaviorism’s superficiality.

Allport went through a dictionary and dug up 4500 adjectives that might be used to describe personality and used them to develop a more contemporary language for describing people. He demonstrated that these terms could be used reliably and consistently and had objective and predictable relationships to one another. His student, Walter Mischel, however, tossed a wrench in the plans when, as stable and reliable as they were, Allport’s terms didn’t predict behavior very well.

Perhaps you have seen one of the myriad internet articles about how poorly humans score at detecting lies in the laboratory. Although most of us believe we are pretty good at detecting dishonesty, when systematically examined in the lab, we tend to be pretty bad at it. Mischel’s work did the same number on Allport’s traits, and eventually a body of work arose testing trait theory that showed that many traits were more dependent on context of the rater and the rated than on intrinsic and stable dimensions of personality or their associations with behavior.

The Rise and Fall of Cognitive Consistency Theory:

In Chicago in the early 1950’s a group of UFO enthusiasts formed a cult, The Seekers, around a woman who was practicing automatic writing, Dorothy Martin. Leon Festinger, a professor of psychology at the University of Chicago at the time, got wind of this group and infiltrated it with a participant observer. Dorothy had predicted that flying saucers were going to offer the faithful an opportunity to flee the planet ahead of a worldwide catastrophe. In the anxious conditions hard on the heels of a catastrophic world war and in the midst of the warming Cold War, this was believable enough to some that her followers intended to rendezvous with the spacemen and escape to a better life.

Festinger assumed that the deliverance that Ms Martin predicted would not come to pass as expected, giving him the opportunity to test his new theory of cognitive dissonance. Festinger thought that, contrary to common sense, the cult would not break up when the predictions proved inaccurate, but that many would act even more committed. Those who had already acted on their beliefs to attend this rendezvous would redouble their beliefs and try to rendezvous again because of the disconfirmation. And some in the cult were so committed after the second failure of aliens to appear that one couple sold their home and the bulk of their possessions despite two previous no shows! In 1954, Festinger, Schacter and Riecken would publish one of the most influential books in modern psychology, When Prophecy Fails, articulating the now ubiquitous theory of cognitive dissonance. Festinger would go on to postulate the idea that humans functioned under a large and consistent network of values, attitudes, and behaviors.

Some of the same research that rolled back illusions about stable predictive traits also brought down cognitive consistency theory. Subsequent research intended to prove this theory instead showed that often people did not actually behave as their attitudes expressed in the laboratory and on surveys said they should! And neither were their attitudes all that scrupulously consistent. A contemporary example would be evangelical biblical literalists who are very concerned by people’s behavior that is not consistent with Biblical morality but who are enthusiastically supporting a Presidential candidate who openly breaks the Ten Commandments. Such examples are not just a characteristic of the political right! Many liberals and progressives are all too ready to curb freedom of expression if they think that speech is correlated with bad behaviors despite avowing personal freedom. These kinds of inconsistencies are the rule in human attitudes research, not the exceptions.

Logic and Emotion are Inseparable in Neuroimaging:

In fact, even the distinction between rational ideas and emotions gets fuzzy if you look too closely. After many attempts to separate logic and emotion, evaluation of neuroimaging suggests that statements that are clearly identifiable as one or the other are nonetheless processed by the same portions of the frontal cortex and amygdala which were heretofore though to be the physical seats of logic and emotions respectively. The neural pathways may be slightly different, and their connections surely are, but the brain does not have simply identifiable regions that separate logic and emotion!

All of this looked rather consistent with the work of Dr Freud, but, as told elsewhere in this blog, when Evelyn Hooker made an objective attempt to assess how effective projective testing based on Freudian theory might be in sorting out the differences between homosexuals and heterosexuals, not only did the homosexuals fail to look more pathological on the tests, but the best psychological test administrators could not sort out the gay men from the straight ones using only their test responses. If self-report couldn’t be trusted, it is quite possible that projective testing was little additional help.

Free Will is Sometimes an Illusion:

Psychologists have also found that people’s seemingly free choices can be totally controlled by magnetic brain stimulation to the motor area of the brain. Neto-Brazil et al (1992) reported that subjects could be induced to extend either their right or left index finger without any subjective sense of preference or impaired volition. While it is a fair criticism that simian neurophysiology evolved in circumstances in which magnetic stimulation was exceeding infrequent, and thus human behavior in a natural setting might still be free absent experimenter manipulation, it is clear that the subjective self-report of freedom of choice is an illusion that is not related to the statistical likelihood of making those choices! If we can produce this in the laboratory, there is strong reason to worry about ‘natural’ behavior even if it is more complex and nuanced and not deliberately manipulated by artificial means. Nonetheless, I am serene in my assurance that I posted this paragraph freely! Trust me!

The Wisdom of Solomon Asch:

In 1956, Solomon Asch reported a series of studies in which a research subject and 3-5 confederates of the experimenter examined lines drawn on index cards of either the equal, or substantially different lengths. When asked to compare lines of obviously different lengths, three quarters of subjects would tend to conform to the group opinion even for obviously different line lengths if all the previous confederates had said they were equal. About 25% of the research subjects were impervious to the siren call of conformity, but 75% succumbed sometimes, and 5% never gave a non-conforming response. Asch concluded that the need for social conformity outweighed the real differences in line length. This work and the behavior of German officers during the Nuremberg trails inspired Stanley Milgrim’s experiments in obedience to authority.

The Milgrim Experiment:

“Don’t follow leaders and watch your parking meters.” Subterranean Homesick Blues — B Dylan

In the early 1960s, Stanley Milgrim conducted a series of psychological studies off campus from Yale University in downtown New Haven Connecticut. In an elaborate series of experiments designed to explore obedience to authority, subjects were recruited to an unprepossessing downtown storefront where experiments allegedly exploring memory and learning were being conducted. When the subjects arrived, they were briefed and instructed to administer electric shocks as exploration of this method’s ability to accelerate learning. They were then given the responsibility of administering increasingly painful shocks to a confederate of the experimenter who was strapped to a chair. As the confederate made errors the subject would give increasingly painful shocks until the confederate, who appeared to be in discomfort asked for the experiment to stop and for release. At that point, the research subject often asked the experimenter for permission to stop, which was denied. Despite labels on the apparatus that indicated “very severe shock’ was being administered and obvious signs of distress from the confederate, 65% of the research subjects turned the shocks all the way up before the experiment was terminated.

This research earned Milgrim both a letter of censure for violating his ethical obligations to research subjects, and a prize for the best social research project in his first year of reporting the results. In addition to its obvious benefits it advancing our understanding of the prevalence of obedience to authority, it also initiated important protections for the rights and welfare of research subjects. For the purposes of this essay, however, both Solomon Asch’s and Stanley Milgrim’s work not only challenge ideas of trait theory, but also raise questions about how trustworthy our closely held notions of conformity, independence, obedience and empathy really are.

Response Biases:

The cumulative effects of these discoveries were pretty well understood 35 years ago when I took advanced survey methods. We spent an entire unit on how to cope with the problem of response biases in test construction. Generally, the top 4 response biases are:

1) Acquiescence. When in doubt – and even when not in doubt – respondents prefer to say “yes”.

2) Social Desirability. Respondents endorse responses that they feel display themselves favorably.

3) Intelligence. Many measures operate differently for smarter subjects, constituting a covert intelligence test, rather than measuring whatever the researcher intended.

4) State Anxiety. Responses are determined by how anxious the respondent feels instead of what the researcher intends to measure.

All scientific instruments need to be built to neutralize the possibility that they are measuring something other than intended, but these are the four usual suspects in social research and test construction. Acquiescence can be handled by reversing questions about half the time such that yes doesn’t always affirm a positive. “I like dogs” and “I hate canines” are sufficiently different questions that it may be worth using both in a survey. Social desirability can be combated by framing questions so that there is no answer appears more desirable than any other. In the immediately previous example, the question “I hate canines” is poorly framed with social desirability because it is socially undesirable in most western cultures to hate things. “I dislike canines!” would make a somewhat better wording. Intelligence can be reduced as an explanation if all questions are simply and clearly stated in language well below that used by most respondents. For that reason, ‘canines’ is a poor word relative to ‘dogs,’ which is more universally understood. And care should be taken in asking questions that would arouse the average respondent’s anxiety. In the above example, I wisely declined to ask about whether anyone liked big scary dogs!

Note that even though well-trained researchers can construct tests and surveys that get around these problems, the existence of response biases remains a challenge to the idea of self-reporting. If self-reports are so prone to such distortions, even well-asked, how valid can the answers to such questions be?

The Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory remains one of the most commonly used actuarial personality tests. It pioneered the use of special scales to check on the validity of its clinical measurements by assessing how open or defensive a given respondent was in taking the test. If a person was too defensive or refused to state anything socially undesirable about themselves, then the interpretive significance of their performance on other scales was diminished, or even invalidated. While validity scales cannot correct for response set distortions, they can at least detect defensive individuals who might not be candid. As such, they are more useful in testing for individual differences than assessing the prevalence of attitudes or behaviors in a sample of respondents.

“What’s a mother to do?”

Now that I have thoroughly demolished a host of common assumptions that we enjoy about ourselves, it is an inevitable question what the psychotherapeutic arts can do to cope with this massive burden of subjective unreliability. It is perhaps completely unsurprising that my summary of solutions strongly resembles a very concise primer of basic psychotherapeutic interviewing principles!

One of my favorite bumper stickers reads “Why question authority? They don’t know either!” And there is something in this quip which captures the essence of the post-modern solution! If no one’s account is all that reliable, there is no refuge in expertise as a superior authority to the subject’s own report.

There is strong evidence that there are some states and conditions that defeat the idea that an individual’s self-report is inevitably the best estimate of their experience. People lie, they are compelled by drugs, alcohol and altered states and magnetic electrodes wielded by crafty psychological researchers. They hide, conform, and avoid conflict. Clients often fail to know themselves, but we are nonetheless able to tell the difference between people with low and high degrees of self-knowledge. Most of the time, fallible as it is, a person’s account of their experience is the best evidence we can get in most clinical situations. We do not have a good substitute for closely observing where their behavior deviates from their statements about themselves.

Consent can approximate being fully informed, even though humans are highly fallible at foreseeing the full implications of their actions. We rarely decline to conduct psychotherapy despite the fact that we are open to the possibility that the results of therapy can’t be fully foreseen by ourselves or our contracting clients.

Continuous communications provide ample opportunity for self and other correction when our capacity for self-report and freedom of choice breaks down. We humans are social animals built to learn about ourselves in the mirroring of others. Our nearest simian relatives do many of the same behaviors we do. So intimate communications are a great place for checking our subjective experience. Intersubjectivity has failures, but also many successes.

And we can suspend our clinical judgment and ask open-ended questions while we try to understand the discrepancies between our understanding of a client and their self-report.

You might be more surprised to notice a resemblance between the recommended best practices here and the values and boundary rules of many kinky communities. Ground rules like don’t make assumptions, allow people to present as they wish, communicate continuously, and use continuous informed consent are prominent values in many kink communities. That is not a mere coincidence. Kink does not have to be an intimate experience, and it is possible to play with people one does not know or understand well. But if a person seeks to find a mate or intimate partner in these communities, the rules of communication must provide room for intimacy to develop. Many of the same behaviors promote emotional intimacy on the consulting room and the dungeon.

The Good News:

Psychotherapy cannot begin with great intimacy, but it is very unlikely to be successful if intimacy doesn’t grow in the therapeutic relationship. So many of the things that make all relationships successful underlie success in psychotherapy and in kink. Although they have important differences from mundane relating, they are not alien ground. The chief differences from everyday relating is that they have with in common with each other have to do with emotional risk and intimacy. You cannot know each other and get accepted for who you are in intimate relationships without being as honest about that as you can, the folly of self-report notwithstanding.

The Bad News:

Intersubjectivity and social construction of reality also mean that any identity you offer to others is a bid for acceptance, and you can never be fully complete only in your own opinion. Your self-report is the starting point, but you are not fully who you say you are if no one else agrees to it. “Consent counts!” has the disquieting implication that you are not who you say you are until some important group of other people can be persuaded to agree.

“Most social acts have to be understood in their setting, and lose meaning if isolated. No error in thinking about social facts is more serious than the failure to see their place and function.” Solomon Asch in Social Psychology 1952

© September, 2019, Russell J Stambaugh, PhD, Ann Arbor, MI