What if I told you that a marginalized genre fiction writer penned an indifferent serialized story that became an overnight best seller and helped change the world, you would probably think I was hyperbolizing the achievements of the 50 Shades series author E. L. James. That fan fiction is its own ghetto, and romance novels are primarily a marginalized female genre would be easy to concede. The critical response to 50 Shade of Grey has been indifferent at best and often scathing. There is no arguing with the huge numbers (over 125 million copies sold in various formats) James has put up in an ever shrinking literary market where, according to Pew Research, less than half of Americans will read 12 books for pleasure in the next year. That the commercial success of the 50 Shadesseries might change the social acceptance of kink might seem a stretch. But I am not talking about E L James, or at least, not only about James. In 1851-2, a very similar feat was accomplished by Harriet Beecher Stowe.

|

| Harriet Beecher Stowe (1811-1896) |

In the early part of the 19th century American Protestantism underwent a great renaissance, the Great Awakening, with a rise in evangelism, many new denominations, and increased church attendance. This revolution was not just about new doctrine, but also social reform movements. Chief among these were abolitionism, and temperance. Ironically, many of the present debates about hypersexuality and ‘sex addiction’ can be traced to religious social activism that began at this time, but this essay will focus on the pivotal work of the abolition movement, Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

|

| Lyman Beecher (1775-1863) Started The American Temperance Society, and ran Lane Theological Seminary until it failed in 1852 |

Harriet Beecher Stowe was the daughter of a Lyman Beecher, the 7th of his 13 children several of which went on to become influential clergy. He was the founder of the early temperance movement and a divisive figure in Protestantism, eventually splitting the Presbyterian Church. In the 1830’s he moved west from Connecticut to Lane Theological Seminary near Cincinnati, then a thriving bastion of the westward expansion. His daughter would spend many of her developing years at Lane Seminary educated to typically male standards prevailing there, and eventually became a prolific writer. From her location right on the Ohio River, and through her family’s work in a seminary right at the border between the North and South, Harriet was able to learn of the realities of slavery.

|

| Henry Ward Beecher (1813-1887), Stowe’s brother. Ardent abolitionist, unionist, and womanizer, he later ran afoul of Victoria Woodhull leading to a hugely publicized adultery trial. |

When the War Between the States began, Kentucky would not actually join the Confederacy, and from the bluffs on the north bank of the Ohio River, Stowe could not see slaves out toiling in the fields. Both Kentucky and Southern Ohio were culturally similar to the South, but the land was not suitable for cotton cultivation and typically smaller farms, horse pastures and mountain tobacco plots did not lead themselves easily to plantation economics. Stowe mainly learned from the southern coreligionists seeking Presbyterian ordination at Lane. The river that flowed by her door was the closest thing our nation had at the time to a superhighway and it did flow through ideal cotton country through portions of Arkansas, Mississippi and Louisiana on its way to New Orleans, the Southern United States largest and most active port. So Harriet Beecher Stowe did have a window on plantation slavery that most northern abolitionists lacked, though she was still not researching her novel touring actual plantations.

Although her father was by no means an abolitionist, Harriet was greatly moved by the plight of escaped slaves. The success of the Underground Railroad spurred developing US law that protected property rights of slaveholders and this escalated the conflicts. In 1851 she began serializing Uncle Tom’s Cabin in a newspaper. It ran from June of 1851 to April of 1852, and was followed in book form. The first edition run of 5000 quickly sold out, and became a runaway bestseller, eventually becoming the second best seller in the US in the entire 19thcentury, behind the Holy Bible. While Stowe did not become super wealthy as rapidly or dramatically as E. L. James, this was plenty of money for comfortable life. But what of her purposes as a reformer?

|

| One of the many editions of Uncle Tom’s Cabin |

Considering its huge popularity, Uncle Tom’s Cabin was not an immediate critical success. It was written in the then popular sentimentalist tradition, a marginalized genre of fiction in which female writers wrote works that were read by a primarily female audience. Uncle Tom’s Cabin was criticized as maudlin, melodramatic and emotionally sloppy, and not just by Southern literary critics who recognized the book’s potential power to mobilize Northern opposition to slavery, but by critics who demanded more elevated non-genre fare. Today it would surely be viewed as manipulative. Its impact was nevertheless profound.

Whatever its critical demerits, Uncle Tom’s Cabin had tremendous social power. Many northerners who opposed slavery on religious grounds had no direct experience with slaves. Even in the south, only a tiny percentage of the land-holding white population held sufficient property to have direct contact with the kind of plantation slavery Stowe depicted. With only print mass media, scant photography, and little recreational travel on an American railroad system that was still building out rapidly, a great many people were to learn more of slavery through Uncle Tom’s Cabinthan could ever encounter it directly. And the narrative it provided, that slaves were dehumanized by being treated as property, rather than being civilized happy and productive because of the structure provided by the owners, had great resonance.

So disturbing to the southern landowner class was “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” that southern writers almost immediately created counter-propagandistic accounts of the loving, stable, patriarchal and solicitous concern of slave owners for their slaves to counter the wicked overseer Simon Legree in Uncle Tom’s Cabin. But an effusion of books could not diminish Harriet Beecher Stowe’s influence, or counter the economic or political cascade towards intensifying conflict over slavery. But such was the power of this discourse that the myth arose that Abraham Lincoln first met Stowe early in the Civil War, he said ‘So here’s the little lady that started this great war!’ While this quote is probably apocryphal, Uncle Tom’s Cabin did bring some sense of slavery to the large percentage of the US population that had little real contact with the institution, and amplified the sermons of the abolitionist preachers. The US Civil War may have been determined by material, economic and political causes I have pictured, but Uncle Tom’s Cabin definitely shaped the discourse.

This contribution was not accomplished without a price. Whether through the over-drawn caricature of the sadistic overseer, the creation of the social stereotype of the conflict avoidant and protective Uncle Tom, or the depiction of Negroes in need of protection that was as patriarchal at its core as the ideological defenders of slavery, Harriet Beecher Stowe’s depiction of antebellum southern life traded in stereotypes that have persisted ever since. Some of us are old enough to remember charges within the civil rights movement of ‘Uncle Tom-ism.’ However, neither is it obvious that racial equality would have been effected had Stowe matched Jane Austen in her psychological sophistication.

|

| E L James, 50 Shades of Grey, and leather pants |

But the critical discourse over Uncle Tom’s Cabin might place some of the criticism of Fifty Shades of Grey in a different context. If being ghettoized, marginalized, imitated and counter-propagandized didn’t prevent Uncle Tom’s Cabin from having a large social impact, perhaps the timing and commercial success of E. L. James’s works will be more influential in the de-stigmatization of kink than we expect. Stowe’s case study is a perfect illustration of how we can expect reform not from the heart of the dominant culture, but from its borders. Social research has long shown that women harbor submissive sexual fantasies that are not politically correct. We have known this since Nancy Friday’s My Secret Garden, (1973) that women’s actual fantasies do not correspond very well to conventional mythology. So it should not surprise us that some measure of kink discussion and acceptance came from the literary hinterlands of fan fiction where themes of power, sexuality and transgression are commonly discussed. To be transformative, a work need not be mainstream, possess revolutionary intent, or accepted aesthetic depth. It is the discussion the work provokes, not just its intrinsic attributes that do the work of reform. Fan fiction is a place where that discussion regularly happens.

|

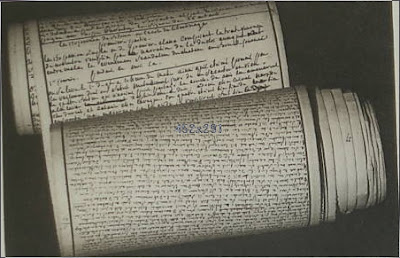

| If you find 50 Shades hard to read, it could be a lot worse: the original manuscript of de Sade’s 120 Days of Sodom, written in blood and feces and rescued from its hiding place in prison. |

But before you dismiss the 50 shades series as bad books inspiring a bad movie that depict the world of kink badly, it is worth asking the question of whether this somehow constitutes a poster case of the aphorism that there is no such thing as bad publicity. A great deal of this discourse about BDSM is not very favorable, and not very informed, and certainly isn’t directly in the interests of the kink community, or even the explicit de-stigmatization of variant sexuality. BDSM interest is handled unrealistically and melodramatically in the series. Nevertheless it has provoked increased interest in BDSM social groups and many new people showing up and asking questions about kink. And the discourse, while hardly kink-friendly, is more open than it was two years ago before the publication of the series.

50 Shades may be poor BDSM, but then so again are the works of Pauline Reage, Leopold von Sacher-Masoch, and the Marquis de Sade dangerous depictions of kinky life. Many readers note that that danger is inseparable form their power to arouse. No safewords; character and context are sometimes dispensed with, and other times wooden and stereotypical. Even when psychologically sophisticated they are incomplete and provide poor context for constructing a satisfying kinky life. They share many of the defects of porn in their destructive assumptions of a happy contextless sex life. Yet works by these authors had much greater impact on the world of ideas than their content had on BDSM practices. 50 Shades is like Uncle Tom’s Cabin in that it provoked discourse that has moved people’s attitudes without being a very accurate depiction of its subject.

|

| Doing their best to make a contextless BDSM life look shinny: Nina Hartley and friend. |

Fifty Shades has greatly increased the discussion of kink, and not all of it was red meat for socially conservative talk show audiences to devour. The book has linked sexual submission with sexual heat for many readers, and that has generated much curiosity that goes beyond mere fantasy. Those of us who are used talking about sex recognize that fantasy and experience are very different sex modalities, but discussion around the books does provide for communication about this that does not often occur in heteronormative sex discussion. Even in books that reflect the rather atypical story of a man who is into kink primarily to resolve intense childhood dynamics of abuse, the volume of increased discussion of contracting, the importance of consent, and Anastasia Steale’s eventual insistence on withholding consent constitutes sex positive context for those discussions. While there is poor empirical validation of how many American’s ever visit BDSM social clubs, there is strong anecdotal evidence from all over the country that curious new members are coming in. All of this suggests a modest level of de-stigmatization of kink has been accomplished by the novels that transcends their literary merits. Even where BDSM is pathologized, and Anastasia must struggle with Christian’s villainous abuser, Christian is not rejected for his kink preferences. This acceptance, and the open embracing of readers’ fantasies, creates an accepting meta-context that transcends the poorly constructed melodrama around struggling to free Christian from his dark past.

What if this prediction that 50 Shades has really made it possible for many people to explore kink who were interested but dared not open themselves to it before proves true? I caution that all these potential benefits of The 50 Shades works does not suddenly constitute the final victory in the social acceptance of kink. The kinds of genre-based conventions that make 50 Shades appealing make it a flawed basis for evaluating one’s readiness to opt for a kinky lifestyle. The world of kink is much more diverse, more polyamorous, more exhibitionist and voyeuristic than 50 Shades. Pain feels differently in the flesh than in fantasy. The social conventions and norms of scene participation are poorly communicated in the novels, and the learning curve can be steep. But motivating people to communicate about these, whether in their relationship or with kink educators, is a powerful source of improved self-knowledge and this can only improve people’s chances of achieving greater satisfaction relative to reading curled up in the bed after their partner has fallen asleep. Perhaps 50 Shades is a powerful example of the alternative to slut shaming in that Anastasia can try some sexual experiments, some of them not especially smart, and learn what she desires without becoming labelled. That message is more important than the whether the kink is properly safe sane and consensual.

All of which poses a challenge for kink and for advocates of sexual freedom. If, like porn, a romantic novel sparks considerable interest and waves of young new adherents present at kink groups, these people will change the culture. This happened to the psychedelic drug culture, which started with genius members of the intelligentsia like Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert (later, Babba Ram Dass) who took drugs for existential exploration and quasi therapeutic purposes. They were followed by college intellectuals and Ken Kesey’s Merry Pranksters, who craved intensity of experience as much or more than self-knowledge. As drug use became even more widespread, eventually many young people were taking them for escape and a burnout culture arose that was mainly one of disaffection and hedonism, think Beavis and Butthead. While all of organized BDSM is not bound to go the way of Cheech and Chong simply because of James’ novels, the influx of new members does threaten to challenge kink’s conventions, and as kink becomes less marginalized, some meanings become co-opted and culturally expropriated. Even before 50 Shades was published, there was much discussion in kink theory about whether there had ever been an Old Guard tradition and whether its demise and resurrection were a good or bad thing. Such discussion is likely to be repeated.

|

| The Merry Prankster’s psychedelic bus. If Tom Wolfe is to be believed, the Pranksters were risk takers trying to see how high they could get. Is this a good model for kink? Doesn’t sound very SSC! |

The challenge of de-stigmatization lies in shaping the discourse in even more accepting ways. But it is powerful to remember that a group of romance novels notably lacking in any effort to reform, got the conversation started in many new places. Like Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the timing was right for change for 50 Shades of Grey. We cannot easily see the evidence of its help to our efforts until the results are receding in the review mirror.

2015, Russell J Stambaugh, Ann Arbor, MI All rights reserved.