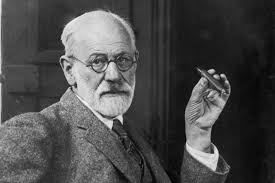

Sigmund Freud is the towering figure in the invention of psychotherapy and is one of the most important thinkers to contribute to Western notions of modernity. Born in Moravia (now part of the Czech Republic) in 1856, Freud’s Jewish father was a moderately successful textile salesman who brought his family to Vienna and paid for his son’s education at the gymnasium, thus qualifying Sigmund to enter the University of Vienna. Sigmund studied first medicine, then neurology, training with some of the most famous Swiss and French neurologists of his day and became a lecturer at the University of Vienna. Throughout his tenure there, Freud was very much split between teaching, his private practice as a psychotherapist, and his prolific career as a writer. An inveterate publicist and promoter of his ideas, he invented psychoanalysis, organized it as a clinical and academic discipline, and wrote seemingly tirelessly about its clinical technique, theory, and larger societal implications. Although Freud was not religious and never practiced as a Jew, he was a pillar of the Viennese social community and married Martha Bernays, the daughter of a prominent rabbi from Hamburg . From 1902, he held continuous weekly meetings about psychoanalytic topics, and in 1905, he founded the International Psychoanalytic Association. The so called Standard Edition of his works translated into English by James Strachey runs 24 volumes and thousands of pages.

Between the publication of The Interpretation of Dreams in 1901 and his departure from Vienna in 1938, Freud’s psychoanalytic circle anointed all the greatest thinking about therapy. Carl Jung, Alfred Adler, Otto Rank, Sandor Ferenczi, Karen Horney, Marie Bonaparte, Erich Fromm, Lou Andreas Salome, Harry Stack Sullivan, Wilhelm Reich were all pillars of the International Psychoanalytic Association at one point or another. In his later years, Freud increasingly turned his attention to social phenomena like religion, education, and the relationship between society and repression. Just after the Anschluss in which Austria was absorbed by Nazi Germany, the Freud family emigrated first to Paris, and then to London, by June 4, 1938. By the time he left Vienna, he had suffered from the effects of mouth cancer for more than 15 years, the disease was initially diagnosed in 1923 and Freud went through a long and difficult history of treatment. In September of 1939, without further treatment options and in the face of weakness and chronic pain, Freud arranged for legal physician-assisted suicide on September 23, 1939 at his new home in Hampstead, London.

Anna Freud, who assumed the intellectual leadership of psychoanalysis after her father’s death, was so embittered that she did not return to Vienna even for visit until 1972. Because of that and difficulties associated with his emigration from Vienna and the death of Sigmund’s four sisters in Nazi concentration camps during the war, Freud’s extensive library, archeological artifacts, and clinical consulting room were recreated and kept in London and never repatriated to Vienna after his death.

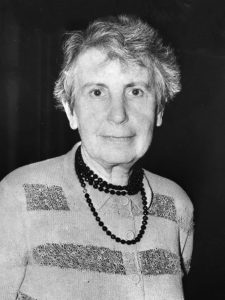

|

| Anna Freud (1895-1982), in 1957. |

Freud not only invented psychoanalysis, he was a prominent mythologizer of the field. He constantly portrayed psychoanalysis as victimized by the very forces of repression that he was striving to overcome through psychoanalytic insight. As a consequence, of this dramatic struggle, the popular imagination about Freud is plagued by a variety of hyperboles and exaggerations about Freud’s already immense role in modern thinking. I will proceed to break a few of these down, and try to put his real contributions into a larger perspective:

Myth #1. Freud Invented Talk Therapy:

Physicians had been talking to their patients for years and already realized that reassuring conversation, non-medical advice, patriarchal solicitousness, and even placebos, could have powerful effects on patient health. Mesmer and Charcot had already demonstrated powerful effects from talking interventions like hypnotism. Freud invented psychoanalysis, the termhe used for his particular theoretical and technical rationale about what made the talking cure work. So Freud did much to popularize and refine the talking cure, but did not invent it.

Myth #2. Freud Set Out to Invent Talk Therapy:

Freud thought of himself as a neurologist, and imagined that the clinical phenomena he was seeing in therapeutic conversations with patients were neurological, not psychological phenomena. Until 1900, Freud was engaged in an elaborate and failed study, the Project for a Scientific Psychology, in which attempted to describe mental phenomena in neurological terms. This effort was premature and awaited technological breakthroughs, including the identification of neurotransmitters and CT, PET, and fMRI imagining techniques that were not developed until long after his death. Were Freud working today, he’d probably be seeking NIMH grants for brain studies using the latest scanning technology!

|

| Freud’s couch ready for it’s scan. It could happen! |

Myth #3. Freud Was a Cocaine Addict and His Work Was Nonsense Because of Chronic Intoxication:

|

| Turn of the century apparatus for administering the 7% solution of cocaine. 93% was saline. In 1974, Nicholas Meyer penned a novel that threw Sherlock Holmes and Sigmund Freud together on a case. |

Freud was an enthusiastic early user of cocaine and wrote rhapsodically about its stimulating effects. At the time (late 1800’s) its addictive properties were not known, and laws had yet to be passed against its use. Freud’s extensive body of writing has withstood the test of time, and while some of it is clearly wrong, it is much more limited by his times and the extant medical knowledge and social conventions, than by the researcher’s use of psycho-active drugs. It should be noted that Freud’s cocaine use was conventional in his time, but would constitute impaired professionalism in the modern context. Recognition of the dangers that opiates and cocaine posed led to the Harrison Act of 1911 in America . That legislation established non-medical uses as illegal, commenced limited regulation of the pharmaceutical industry, and self-prescription would eventually be forbidden. European countries passed similar laws around this time as well. It is estimated that around the turn of the century, 1 in 20 Americans was addicted to patent medicines that contained alcohol, opiate derivatives, and/or cocaine. Freud may have remained vulnerable to self-prescription due to cocaine’s analgesic effects it most likely had on the pain associated with advancing mouth cancer.

|

| Snake oil. Yes, it sometimes contained the oil from freshly squeezed snakes! The active ingredients, however, were cocaine, alcohol, and opioids. |

Myth #4. Freud Invented the Idea of the Unconscious:

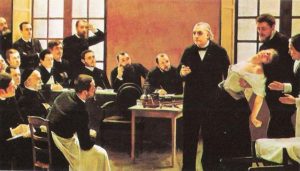

|

| Jean Martin Charcot presents on hysteria circa 1870. |

Actually, the idea of the unconscious pre-dated Freud’s work and the idea that people were not fully aware of what they were thinking was in common currency during Freud’s training as a neurologist and the staple of early learning theorists. Franz Mesmer’s ideas of animal magnetism were known to be involved in hypnotism and, relied on the existence of an unconscious. Similarly, Jean Martin Charcot, the founding father of modern neurology, came to believe that repression was involved in hysteria and he demonstrated how memories could be lost and recovered from the unconscious under hypnosis. Freud did, however, invent and popularize the idea of the dynamic unconscious as a mental agency in which socially intolerable instinctual impulses were kept from consciousness lest we think badly of ourselves and violate social rules. It is the Freudian model of the unconscious that undergirds popular thinking today about our mental lives and self-concepts.

Myth #5. Freud Thought Everything Was About Sex:

|

| Austro-Hungarian machine gunners in World War I. Freud served his country during that war, and saw the psychological consequences of industrialized combat. Maybe not everything was about sex. |

Although this myth seems difficult to refute, it is important to realize that even in its most extreme form, Freud’s position was more nuanced. In his initial theorizing, sex played an exclusive explanatory role, but Freud was not speaking of foreplay, intercourse, or suspension bondage. For Freud, sex was an underlying human motivation derived from direct but largely unconscious instinctual expression. It was a natural consequence of our Darwinian animal nature and our evolutionary purpose to pass our genes on to the next generation of human beings. Libido, that natural biological energy that sometimes resulted in direct mating behavior, got sublimated into all other social acts like going to school, attending church, everyday labor and social interaction. So for Freud, behaviors that didn’t look sexy at all were energized by underlying sexual motives. Later, Freud also hypothesized a death instinct which was equally mutable and unconscious. Most writers after him have preferred to translate his death instinct as ‘aggression.’ Both of these instinctual drives were balanced in their social expression by the conscious abilities of the person, and their internalizations of social rules, norms, ideas and values, so libido was only expressed in directly sexual ways a small percentage of the time, even for the sexually preoccupied.

Myth #6. Freud First Recognized the Importance of Infantile Sexuality:

This myth partially depends on what you believe the importance of infantile sexuality really was, but it is certainly true that the Victorians, including their physicians, did not recognize that children experienced sexual feelings and did not recognize childhood behaviors as sexual in nature. In fact, the Victorians didn’t recognize that people were sexual throughout the life span, dramatically understated female sexuality, and struggled to accept Darwinian ideas. Thank heavens we are all past that today! Victorian physicians who operated vibration clinics as a way to release stress in women would not have been able to do so, had the full sexual nature of the relaxation response been properly recognized for what it was!

|

| Albert Moll (1862-1939) German psychiatrist and among the first to recognize childhood sexuality. |

Albert Moll was the turn of the century sexologist who was first in advocating for the recognition of childhood sexuality. When Freud advanced his own developmental theory that suggested the sucking, defecation, urination, and Oedipal behaviors were all manifestations of infantile libidinal expression, this idea was revolutionary. But you have to think the proliferation of anti-onanistic interventions and ideology, from sports advocacy to gender-segregated education to aphorisms like ‘Idle hands are the devil’s playground!’ reflected some Victorian suspicion that children weren’t all that innocent. Even today, the role of direct sexual expression in childhood is largely under-recognized, and this underlies social phobias around comprehensive sexuality education in the United States.

Myth #7. Freud Was the First to Recognize the Importance of Bisexuality:

|

| Sorry! This is not the kind of bisexuality Freud meant in his theory. |

Freud probably learned about the concept of libido and its bisexual nature first from Charles Darwin. It certainly figured prominently in Freud’s early theories of sexuality that libido was bisexual in that a child could feel love for both the same and opposite gendered parent. If Freud had encountered the idea of gender fluidity, he would doubtless have endorsed that love could be expressed by people of any gender towards any other. However, Freud operated in a bi-gendered social world, and his theory had to account for the obvious clinical observations that children loved both parents and were in conflict about it. However, if Darwin came first with the theory that libido could be expressed across gendered lines, Freud’s theory did not really address behaviorally bisexual sexual behavior, which he would doubtless have categorized as homosexual behavior and seen as further proof of his theory. Freud did not really write about bisexuality in the way that we use the term today.

Freud did accomplish some great things that are probably under-recognized, notwithstanding his role as the most prominent clinical writer in psychology.

Freud broke the philosophical stalemate between Krafft-Ebing’s excessively constitutional theory, that claimed sexual deviance was largely an expression of constitutional degeneracy, and the early learning theorists, or ‘associationists’ like Alfred Binet, who claimed that all sexual behavior was learned. Freud’s theory allowed for a middle ground that allowed roles for instinctual and learned factors.

Freud is best known for his model of what makes talk therapy effective. He did not think that benign paternalistic discussion cured hysterics of their pseudo blindness or paralysis. Rather, he believed these patients inflexibly refocused their infantile sexual conflicts on the therapist and felt towards him as they did towards their fathers. Their guilty ambivalence about loving their fathers and feeling guilty about wanting to supplant their mothers and to do socially inappropriate things with fathers, led to the personal disempowerment seen in their terrible symptoms. By helping the clients to recognize and refocus these transference feelings in the therapy, normalizing them, and seeing that the feelings need not be harmful, the hysterical clients could give up their symptoms. This is the Freudian description of the transference cure. Did it work? At least sometimes, but it was far from infallible. Considering the severity of disability from such symptoms as paralysis and blindness, it could be a big help.

Freud is also associated with a rather extreme version of analytic neutrality that many patients and practitioners regard as emotionally depriving. A look at today’s austere psychotherapy offices suggests the pervasive influence of fears that betraying any portion of the therapist’s personality might become a distraction and interference with the process of transference. After all, if the therapist displays masculine qualities, for example, this kind of reasoning might expect interference with the patient’s possible need to experience maternal transference feelings. If the therapist appears gay, perhaps the client will be reluctant to express heterosexual feelings.

This is no idle concern. When I was in graduate training, there was a famous supervising analyst who was extremely proud of his original and expensive Picasso, which hung prominently in the consulting room in which he saw is clients and supervised his mostly rather impoverished graduate students. The analyst’s presumed need for phallic display was much discussed, and evidence marshalled for his excessive egotism. It was my fortune to never have actually met this person, so I never had the chance to assess any of this for myself, but it is certainly true that his deviation from presumed orthodoxy had a big impact on his reputation.

|

| Freud’s Vienna home and office at Berggasse 19, now a museum. The sign is a recent addition! (stock photo) |

Late last year, I had the opportunity to visit Vienna for the first time. Despite the fact that our tour did not include a stop at the museum that had been made of Freud’s home and consulting room — are contiguous on the second floor of Berggasse 19 on the edge of the Old Jewish section of Vienna — I arranged for a private tour. I knew that Freud had amassed a large number of artifacts collected in the early twentieth century heyday of classical archeology, and had heard these were displayed profusely in his office and consulting room. I was nearly disappointed. Most of his collection had been removed to London after the famous French analyst, Marie Bonaparte, generously donated the rapacious emigration fees the Nazis required of Jews before they would allow them to flee the country prior to the beginning of World War II. Only a handful of Freud’s artifacts were available in Vienna for display, and only the actual waiting room was furnished. But with a keen eye for history, Freud had hired a photographer to make a record of his rooms before his furniture and collections were shipped away. The pictures showed a dense Edwardian riot of pictures and artifacts! Short of stiffly lying on the analytic couch and staring resolutely at the ceiling, Freud’s clients were surrounded by a surfeit of visual stimulation.

|

| The consulting room, replete with artifacts. Yep, that’s the couch back from the fMRI! (stock) |

|

| A tiny fraction of Freud’s collection left behind in 1938 (photo by author) |

|

| Sometime a clay penis is just a penis! (photo by author) |

|

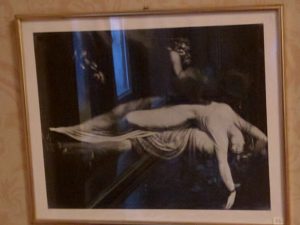

| This drawing hung in his waiting room (photo by author) |

|

| Freud’s Vienna waiting room (photo by author) |

Freud’s consulting and waiting rooms were anything but a modern study in bland neutrality. One can only wonder at the ways in which Freud telegraphed his areas of interest to his clients amid 19th century drawings of swooning classical nudes, every imaginable combination of mythic imagery, and his collection of phallic objects from cultures around the world. Either Freud was completely awash in repression of how all his interests impacted his patients, or he operated on the idea that for transference to be the powerful force that unified every therapy under the aegis of his recommended techniques, it must be so strong that the client imported it willy-nilly into all situations, largely regardless of context, and that propensity made it powerful and neurotic enough to require analysis.

In the next post, I will start to turn to the discussion of Freud’s specific theories about sexuality as they affected thinking about sexual variation. Freud has the reputation of being very judgmental, and Freudians get much blame for the patholigization of kink. Some of this is well-founded, but it would be well to remember that Freud believed that everyone had a dynamic unconscious, had ways in which they were reluctant to completely grow up, and that most under-sublimated expressions of libido were peccadilloes, not pathologies. Kind of like kinks, it the pre-idiomatic sense of that term before it came to be applied to sex variations. We will look at how Freud might have come to be mistaken for judgmental by his successors, despite his demonstrated flexibility and acceptance as a writer. And we will see that in many ways, his critics were correct.

Đơn vị chuyên order mỹ phẩm Hàn Quốc ở tại Hà Nội – TPHCM

ĐƠN VỊ NHẬN ORDER HÀNG MAY MẶC HÀN QUỐC Ở TẠI HÀ NỘI – TPHCM

Công ty chuyên đặt hàng sản phẩm làm đẹp Hàn Quốc ở tại Hà Nội – TPHCM