“Oh, you never turned around to see the frowns

On the jugglers and the clowns when they all did tricks for you.

You never understood that it ain’t no good,

You shouldn’t let other people get your kicks for you.”

“Like a Rolling Stone” – B. Dylan

|

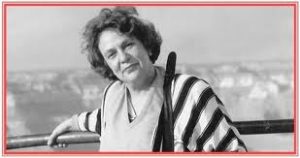

| Mary Gaitskill in 2017, courtesy of the New York Times |

Back in April, the New York Times printed a review of Mary Gaitskill’s new book, “Somebody with a Little Hammer: Essays”. Those of you who have been paying close attention know that Gaitskill is the gifted author of the short story that became an iconic 2002 movie about kink, The Secretary. In this review are included some remarks which serve as an excellent jumping off point for our exploration of a heretofore neglected discussion about kink that emphasizes its dark side. Trite as it is to say, if you have been reading this blog closely, you may well fail to know the power of the dark side.

Despite the extreme good fortune of inspiring a commercially successful movie of our chosen subject, and there is only a handful of such films, Ms Gaitskill was not altogether satisfied with the transition of her oeuvre to the screen. Here I shall quote directly from the Dwight Garner’s review.

“She was displeased with that movie, [Gaitskill] writes. It was breezy and upbeat, absent the darker shading. The takeaway, she writes, ‘is that S/M is not only painless; its therapeutic: It has made both characters more confident, better looking, happier, freer, and self-actualized. Best of all, it has led them straight to marriage!’” How kinky is that?

It would be easy to dismiss this as the conventional culture and its agents; director Steven Shainberg; or the movie’s producers, cleaning up BDSM for mass market consumption. For her part, screen writer of record, Erin Cressida Wilson, won a Sundance Festival Award for this work, her very first screenplay. At least that awards committee didn’t see her work in such a critical light. But if you have both read the short story and seen the film, there is no debating that Gaitskill’s original is truer, grittier, and the more sadomasochistic of the two works. And in the rest of Garner’s review, it Is made clear that Gaitskill has enough sadism to recognize it for what it is in others and that she sees herself as the wielder of those little hammers, a characteristically kinky position. In her own way, she is a social critic.

Kink and the problem of idealization:

|

| Maggie Gyllenhaal in The Secretary (2002) Nice blouse! |

One might be tempted to accept the ‘cleaning up’ of Gaitskill’s story as evidence of the intrusion of ever present fetish elements into kink. And it is true that the movie settings are lovely, Maggie Gyllenhaal’s blouses exquisitely pressed and silky as any fetishist might crave, but hardly consistent with her role as a down and out woman for whom a job as a secretary constitutes social advancement. And kink itself has a somewhat convoluted relationship to erotic idealization. Fetish itself represents the triumph of fantasy over utilitarianism, just as Krafft-Ebing warned us long ago. For those not so inspired, it is difficult to imagine a brassiere, an opera-length glove or a well-turned boot could provoke more passion than a human body expressly designed by eons of evolution to stimulate procreative desire. But fetishism is not simple idealization, as anyone who has encountered its intense specificity can attest. As a teen, I remember reading those letters to Dear Playboy and Penthouse Variations in which fetishists would go on and on about how only barefoot hogtied cheerleaders would do, tennis shoes were completely outré! There is something going on in fetishism beyond simple idealization. But it also takes a certain optimism to believe that, with billions of people engaging in various forms of sexual intercourse around the planet, a specific regime as stigmatized, awkward, often alienating, and sometimes downright dangerous form of human expression could be transformative. Good psychotherapy doesn’t routinely leave bruises except perhaps to the ego. But there is a serious discourse about kink that it isn’t genuine if it isn’t dirty, doesn’t leave bruises, isn’t dark enough, and doesn’t break the rules.

As a therapist, I have encountered any number of people who earnestly represented to me how kink is therapeutic. I believe them, as far as it goes, but I also take such declaration with a large grain of salt. As beneficial as it can be to get what you want, so much human behavior is difficult to explain in terms of simple drive satiation. If it was, millionaires would quit work when their earnings exceeded their initial ideas about how much money they need to spend, rock climbers would quit climbing El Capitan’s sheer face after a single success, and no one would go back to the exact same kind of lover who left them broken-hearted the conclusion of their last affair. Often, exactly the opposite is observed.

|

| El Capitan in Yosemite. Granite sheared by glaciation makes for a steep ascent. “That was fun, let’s climb it again”! Photo by the author |

People do accomplish therapeutic achievements sometimes in kink, but when it comes to shadow play, that process of knowing our dark sides, Freud and Jung, its original proponents, were frighteningly pessimistic about the possibilities. In Analysis, Terminable and Interminable(1937), Freud wrestled directly with the observation that no amount of good psychoanalysis ever made the unconscious go away altogether even though therapy was the process of making the unconscious conscious. For Freud, the process of confronting repression was valuable, but one could never know all of one’s dark side, and there were some impulses it would never be OK to enact no matter how insightful one became about them. Jung was more optimistic, but, looking at the broad cultural sweep of symbols, he was the first to admit that darkness never really goes away. So, what does it mean to ‘play’ with it? It is a pathway with no clear destination.

Organized BDSM tries to create space for darkness to be expressed ‘safely’, and as might be expected, such safety is always a little bit relative. Certainly, it is safer to lie at home in bed masturbating to fantasies of whipping someone and imagine they are loving it than it is to go out and find such a person, acquire the whipping skills to do this safely, get to know the partner well enough that you serve Goldilocks her porridge up at just the right temperature, and suffer the possibility that your partner will flee in terror somewhere in the middle of the process before you learn enough to make the enactment satisfying enough to both of you become sustainable. For all of kink’s confrontation with conventional romantic idealization, there is a genuine dollop of optimism, if not wild-eyed idealization, in such attempts to find kinky liaisons. Yet this was even more true in the past, before the internet, use groups, self-help references and FetLife, and people still attempted kink and succeeded in establishing relationships based upon conducting it.

|

| Vlad,’the Outer’, Putin, Kompromat King, courtesy of Getty Images. “Your secret’s safe with me”! |

Likewise, is it rather optimistic to imagine that one’s life will be greatly improved if someone knows about your kink and accepts it. Surely this achievement would be balm to life-long fantasies and case histories of actual rejection, but it won’t cure your herpes, fill your bank account, or stop your excess drinking. People in BDSM all face stigma over their behavior, and this is a powerful leverage to create community, although kink was stigmatized for years before such communities became common and above ground. And just when it appears that kink is making genuine headway to social acceptance, out comes evidence of the Ashley-Madison hack, or content changes at Fetlife due to credit card billing restrictions, or Russian kompromat trying to out the President of the United States for urophilia, to rub our noses in the fact that doing kink still carries substantial social vulnerability even for out practitioners who have taken reasonable steps to protect themselves from the consequences of the judgments of others. If kink still carries risk, so too is idealization a potential motive to undertake risks in hopes that getting what one wishes for will be as good in reality as one has long imagined only in erotic daydreams. And before we mistakenly attribute this kind of thinking exclusively to kink, please note how similar this kind of idealization is to conventional heteronormativity.

Despite the idealization surrounding fetish, and the optimism that facing risk will bring delights far beyond mundane sexuality, kink is rather contemptuous of conventional idealization. Some of this goes back to de Sade’s confrontation with Rousseau and The Church, but modern kink is dismissive of conventional relationship structures, often surprisingly disparaging of conventional sex behaviors even though conventional folk (and kinksters) pursue them with durable enthusiasm, and kink is often strongly anti-romantic. This is not to say that great loves are not built among kinksters, but many kinks can’t be pursued without eschewing romanticism. While many new submissives dream of finding and all-knowing top, part of a good top’s role description is keeping submissives from over-whelming themselves and that involves denying them some of what the submissives imagine they desire. Tops want to frustrate sometimes, and bottoms desire to be frustrated and give consent to exactly that treatment.

Perhaps stigma can be blamed for this variant of MKIBTYC (My Kink is Better than Your Kink) is an occasional form of socially divisive behavior within the organized kink community, where it is actively discouraged. Here I have creatively perverted the term to apply to kinksters’ occasional tendency to assume superiority over ‘Conventionality’ and use the term ‘vanilla’ as a put down for those who just aren’t hip enough to recognize that kink is ‘superior’.) Cognitive dissonance alone might be sufficient to explain anyone preferring their chosen forms of sexual expression: having paid the costs of such ‘choices’, we are vulnerable to becoming wedded to their benefits. Alfred Adler would have no trouble explaining the shaming of conventionals as a turning passive into active after enduring lifelong shaming of one’s kink, and seeking mastery over the very tools of one’s historically experienced vulnerability.

|

| Serious leisure can be arduous. Rhymes with sex work is real labor. |

Like other areas of human striving, BDSM is sometimes a great deal of work to get to the fun. Dolling up for those sexy fetish pin ups can take many hours of perspiring in latex under klieg lights. Good suspension rigs can take hours to do aesthetically. Playing so quietly that you don’t wake the kids is mostly a turn off that needs to be overcome rather than central to the fun, just as it is for conventional folk. And rough play requires days of self-care long after the endorphins have worn off. For many sensation players, that discomfort is a source of pride, but it still hurts, too.

Similar routine inconveniences plague other forms of what DJ Williams refers to as ‘serious leisure’, and conventional sexuality, too. Serious snow board enthusiasts just as regularly cope with the dangers of taking a spill, or from triggering avalanches. In kink, it is not always sufficient to overcome routine negative emotions, but to court and intensify them to the limit of personal endurance. Kinksters don’t just crave intense orgasms, but intense theater that evokes the darker emotions. Transvestism, cuckolding, and other erotic role play are often shame-based even as participants complain about the social stigmatization of their kinks. People who crave acceptance do so acting on impulses to do the unacceptable. All the conventional fears and disgusts: rejection, abandonment, loss of control, loss of autonomy, loss of freedom, loss of identity, injury and loss of bodily integrity, racism, sexism, infantilization, even evil itself are sometimes directly courted.

Dom/mes and tops, and even submissives deliberately dress to look scary. They play in ways that routinely exceed any hope of plausible deniability. Often, they appear to be showing off. Edge play may be in the eye of the beholder, but being edgy is often seen as a source of status in the communities. While many try to conceal their kinks, there is considerable pride and public esteem to be had in the community for being out about them; often, the edgier the better. This is not a new development, back in the forties and fifties, this was a characteristic of the S/M outlaw motorcycle cultures only a few of whom may have been presumed to have ever read de Sade or Genet. There are many in kink who are openly contemptuous of being normalized, suburbanized, or commodified for mass market consumption. There is a thrill to be enjoyed scaring children, and furry little animals. It is not just sensation-seeking that keeps emergency room staffs telling tall tales of removing gerbils from the occasional rectum. An otherwise respectable kink research organization nicknamed their survey of the health needs of the BDSM communities “The Gerbil Survey” in jest, but playing on precisely this dynamic. An anonymous wag suggested to me that the survey needed a trigger warning!

Kink often embraces things that are despised, dirty and disgusting, from the scut work of polishing boots, to playing with urine and feces, to giving up power and social status, to eroticizing performing the dusting. The problem of idealization is again illustrated by kink eroticism, which tends to veneer over the unpleasant implications of all this. While cinematic depictions of Pauline Reage’s perverse training at Chateau Roissy are invariably clean stylish and resplendent with fetish appeal, cleaning up must be a fulltime job with all the blood, saliva and feces involved in all that slave training. Laundry must be a constant preoccupation despite the scanty attire. And the Marquis de Sade’s writings would have required an army of hired help he could never afford (He may have been an aristocrat, but the Divine Marquis was chronically short of money!) just to clean up after his literary parties, and that is before we get to the problem of disposing of the dead bodies. In reality, the Divine Marquis got into plenty of legal difficulty precisely because, once the judgments made at the height of concupiscence were made, he was unable to clean up after their messy interpersonal consequences. While many of these literary exploits are ‘only’ fantasies, they are willfully messy ones. No one gets pregnant or an STI unless it serves a dark story line. It should be noted that most kinky play does not require unwanted contact with dirt and disgust, but the critical term is ‘unwanted.’ What is the point of having a slave if they cannot be forced to sleep in the wet spot? And how do you know you have surrendered any power unless you have to do things that are genuinely unpleasant?

Jack Morin, reworking John Money’s theory of love maps–or personal erotic templates–could not escape a conclusion that would have nonplussed the late 19th century learning theorists: rather than mainly stemming from early but repressed positive experiences, eroticism in Morin’s view was equally likely to be erected on earlier experiences of fear, loss and emotional travail. Robert Stoller for a time considered that kinks might be caused by childhood medical ordeals. Von Sacher-Masoch believed his love of being beaten by imperious women and his erotic fixation on fur stemmed from a preadolescent experience of being whipped for disrespecting his haughty aunt. Suffice it to say, she had not specifically intended to awaken his eroticism, but to punish him into submission. In this way, turning an oppressor’s intended punishment into a source of lust constitutes a kind of mastery. It restores some personal agency to a story in which the victim rescues something symbolic from maltreatment. These examples illustrate Morin’s idea that sexual excitements come as frequently from ‘troubling’ experiences as they do from routine drive expression or the desire to repeat good times.

In conventional media, kink is just emerging from a period in which sadomasochistic attire is used to denote villainy. Only in the last few years have immaculately suited villains in haute couture duds been opposed by good guys who look like they emerged from the fringes of punk rock (for example, The Matrix)! Ordinarily, a kinky costume is an unsubtle device to spare us the trouble of character development. Kink is bad, and everyone knows it. But not only is it sometimes highly erotic to be bad, it can be socially productive and necessary.

Perversity, creativity, and transgression:

I have pointed out that when Krafft-Ebing first used the term perversion to characterize his kinky psychopathologies, he expropriated a term from moral, religious and legal cultures to characterize erotic preferences that did not serve obvious Darwinian and reproductive purposes. But he was persuading the professional class on the strengths of medicalizing sexual problems when he did so, and trying thereby to ease the acceptance of his model of sexually variant behavior. When the Freudians appropriated this language, the lay understanding of psychoanalysis was that kink was moral perversion. Never mind that Freud believed that we are all perverted in the unconscious, the public understanding lagged the psychoanalytic one. Freud thought perverse desires were normal, even if their expression in behavior was atypical. The part the public understood is that these unconscious desires were in opposition to all good conventional social norms. But Freud laid the intellectual foundation for dramatic philosophical and artistic changes.

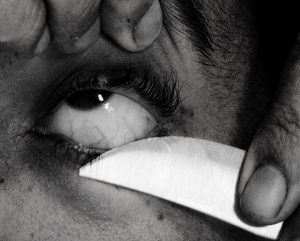

|

| A still from the notorious razor/eye sequence from Un Chien Anadalou (1929), Luis Bunel’s and Salvador Dali’s surrealistic silent film. |

The artistic and intellectual works of Pablo Picasso, Andre Breton and Salvador Dali, Jean Genet, Michel Foucault and Mick Jagger all keep us mindful that the unconscious and kinky were meant to be seen as transgressive, somewhat turning Freud on his head. Kinks aren’t normal, they are shocking, crazy, and bad!

All those towering creative figures were transgressive, as they took a current line of thinking about art and society and overthrew conventional understanding for a new one that emphasized differences with the old ways of seeing and interpreting social reality. Picasso attacked the illusion that experience is contiguous, and reality was concrete. Breton sought beauty in ugliness, and emphasized ways in which the primitive and modern were contiguous, not opposites; he reveled in making scary and incomprehensible narratives. Genet made a mockery of morality; Foucault of professionalism. Where Elvis Presley and Black R & B made the emerging rock n roll explicitly sexy, Jagger reminded us that what makes us hot isn’t orderly, obedient, or even all that good for us. In the 1970 movie Performance, getting in touch with your dark side involves not only hot wax play, but bending your mind, light, and gender before getting you killed. Maybe I’ll skip the cinema this evening and stay in and just listen to Their Satanic Majesties Request on the hi-fi!

|

| A promotional poster for the 1970 movie, Per |

In 1984, Janine Chasseguet-Smirgel outlined this relationship between perversion and the creation of new artistic paradigms in her book, Creativity and Perversion. Although she was careful not to license all kink as creative, she did recognize that the impulse to transgression played a key role in looking at things in new ways. Like psychoanalysis itself, perversion sometimes provided the impulse to look at the world in new ways, and for artistic, scientific and intellectual progress to occur, sometimes the old ways needed challenged or even to be overthrown. The perverse impulse to reject conventional wisdom could provide that motivation and freedom of thought. Although Chasseguet-Smirgel is writing in the Freudian tradition, she goes well beyond Freud in this assertion. Where Freud thought we all had a little perversion in us, erotic variation only became pathology when it displaced healthy sublimations of the (re)productive sexual impulse. Chasseguet-Smirgel suggests that rejection of conventionality could be personally productive and good for society. Carried to its logical extreme, well beyond her limited argument, kink could be, is some cases, the healthiest adjustment for some individuals.

This, of course, is congruent with the argument that Richard Sprott and David Ortmann; Michael Aaron; Chris Donahue, and others who think the first order of business in any therapy of someone coming in disturbed by their kink is to hook them up with the kinky communities. There the client(s) can learn to put their kinks in perspective and profit from the stories of others who are somewhat out about their own kinks. Of course, not all kinks are created equal, and genuine destructiveness and non-consent can limit this for rare individuals, but it rests upon the assumption that out kinksters are healthier than closet ones, which we simply have no data to demonstrate. And, according to the 2014 Consent Violations Survey, 80% of kinksters are not out to someone. So there is good reason to question whether every person who comes in the door is ready to profit from attending BDSM social organizations despite the excellent educational sessions and sound consent ideology to be found there. But plunging clients into the steamy world of social kink where they will learn what they like to the accompaniment of the drumbeat of the lusts of others is a far cry from Freud’s idea that making the unconscious conscious in the quiet meditation of the consulting room will sublimate desire.

Peter Chirinos and Caroline Shabaz refer to the potential benefits of shadow play in their recent book on Kink Aware Psychotherapy. They, like myself, have seen individuals whose kinky ‘play’ takes an important constructive role in their response to traumatic experiences in the clients’ personal histories. Michael Aaron and Dulcinea Pitagora also write about this. Tops and Dom/mes also say that they see this in their play partners. While clinical anecdotes can be highly persuasive, they cannot inform us of whether the client we are just starting to see is engaged in such constructive ways, any more than good epidemiological data can. They do, however, show that others have found such ways can be healthy for some clients.

Transgression is not an unlimited virtue, however. Kinksters can be ashamed and guilty in unhealthy ways about their kinks, or they can take so much satisfaction from their kinks that this overpowers the empathy they need to moderate their behavior with others. Willful rebelliousness is a constant problem for those who try to establish norms and provide safety in the kink community. Recognition of the flaws of authority and conventionality can feed narcissism, romanticize defiance, and fuel anarchy. I side with Chasseguet-Smirgel in her opinion that perversity can be highly adaptive and creative, but it can also be compulsive and reductionist. One hates to imagine two kinky ships devoted to hogtied cheerleader bondage passing in the night over the obstacle of bare feet vs tennis shoes! It should be expected that kinky folk will be conflicted about their perversity, and simply offering permission and affirmation of it in treatment is not likely to resolve deeper internal conflicts.

The best initial place to begin work on perversity in treatment is from a suspension of judgment that does not privilege conventionality. It is important to empathize with the client’s experience of this dimension of their personality, both in perversity’s constructive, neutral, and damaging aspects. The rush to confront or affirm these feelings makes no sense until you can understand the complexity of the client’s relationship to them. That takes time, and is not usually possible in brief treatment. To help with many problems, it is not necessary. But it is often necessary with people who are deeply conflicted about their kinks, and who are torn between their desires to be accepted as conventional but remain fascinated with their darkness. In such struggles, ‘authenticity’ may not lie in identification with our light sides, or our dark sides, but in the interplay between light and shadow, which is often experienced as struggle. In her own way, Gaitskill is trying to tell us that kink is not for the faint of heart. Then again, conducting psychotherapy isn’t for the faint of heart either!

© Russell J Stambaugh, September, 2017, Ann Arbor MI, All rights reserved

This an amazing piece of work Russell.

I know I have told you this multiple times. I think you are a brilliant person. I hope you write more. I learned a lot in this post.

I love the book you discussed for professionals. I do have more questions that have popped up. I will come back soon to ask them.

Ruby B Johnson

you are strongly encouraged to do that, Ruby! I'm sure we each would learn not only from each other, but from the commentary of other readers.

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.