The next four posts explore the problem of using educational touch in the training of sexuality educators, sexuality counselors, and sex therapists. By implication, it covers all professionals and paraprofessionals in sexuality, from medicine to sex workers.

This discussion arises in the context of professional regulation and consumer protection, but it has a much broader context. Given that I have subtitled this blog “Kink in Context”, that deserves a little elucidation up front.

In the face of stigma surrounding sexuality, everyone involved is concerned about their legitimacy. This is why early in this blog I described the work of Erving Goffman and Michel Foucault, this was one of their prime interests. One of the main strategies for solving the legitimacy problem is professionalism. It is commonly believed that professionals are trained, objective, scientific, expert, and put the needs of consumers and the public first, or at least very high in their ethics. Very often, those common understandings are mostly true. But not always. That is why I have included critics of professionalism so prominently in this discussion.

This makes almost every post, including this series, indeed in all of Elephant, a post about ethics. We have discussed the ethics of kink, ethics of psychoanalysis, ethics of sexuality research, and the ethics of the professions. Ethics, of course, is about resolving values conflicts.

In scientific research, the resolution of conflict between different theoretical models is primarily a conflict of data interpretation and the technical problems of arranging for gathering evidence that resolves theoretical disputes. But eventually, even the most abstruse technical problems give way in science to value conflicts when it becomes time to make resource allocation decisions about which test to conduct next. This goes part of the way to explain the uncanny relationship between the scientific insights of any given era to the zeitgeist of that era. The larger thinking of an era influences what scientific topics are regarded as relevant, important, and worth funding; and scientific insights inform how we think about the world and establish how the world works and what is socially important. The unknown gets framed by the known.

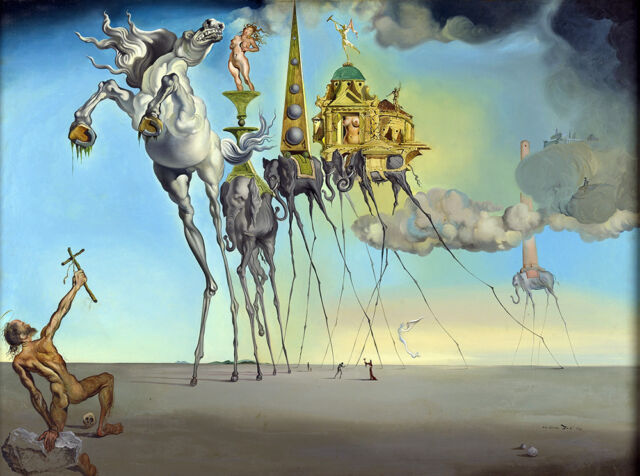

But much of what is important about human sexuality is regarded as emotional and intensely subjective. This has led many to argue that sexuality is not a proper subject for scientific study, and not subject to legitimate professionalization. It has led Nazis to destroy the Magnus Hirschfeld’s Institute for Sex Research, and Tennessee to ban the teaching of Darwinian evolution leading to the theater of the Scopes trial. It has resulted in a serious campaign to institute abstinence-only education in American schools and to defund Planned Parenthood. It has led CDC to become more concerned about expunging language like ‘fetus’ and “evidence-based” from its documents than preparing for the current global pandemic. The fear of subjectivity is a key part of the fear of sexuality. Of course, subjectivity is profound in kink, where the ultimate justification for any consensual sexual practice is, ”I like it!” Think Sancho Panza, Don Quixote’s amanuensis in Man of La Mancha.

I will close with the following conclusion that is largely inspired by the work of Edward D Cheng, JD of Vanderbilt University. What he said of torts applies liberally to all social construction, but the words that follow are my application of his insights about tort law.

The illusion of factual causality:

Sometimes causality can be definitively established. I release my grip on the mike and it drops to the floor due to gravity. But in the social construction of reality the interesting and very common cases do not involve clear consensus as to cause. Often factual causation cannot be established:

Perhaps only correlational or anecdotal data are available.

Perhaps parties cannot agree as to what constitutes data.

Perhaps they agree, but multiple and/or mutual causality creates conflict or ambiguity as to cause.

Perhaps no relevant data exists.

Perhaps data exists, but they conflict.

It is my claim that these are the difficult and interesting cases in torts and in social construction of reality.

In these circumstances, value-free or purely logical social construction is impossible.

If you thought to do value-free psychotherapy based upon a solid scientific foundation was going to be possible, think again. All slopes are slippery. The object of this blog is to help you strap on skis.

© Russell J Stambaugh, PhD, Ann Arbor, MI March 2020