“I’ll have grounds more relative than this.

The play’s the thing, wherein I’ll catch the conscience of the king.” Hamlet Act II, Scene ii

“Battle not with monsters, lest ye become a monster.

And if you gaze into the abyss, the abyss also gazes into you.” Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche as quoted in Alan Moore’s The Watchmen

|

| William Shakespeare (1564-1616) At least as far as we can tell, we have few contemporary depictions of Hamlet’s author. |

While completing my post on the medieval period, I was contemplating the difference between the use of the religious devices designed for penance for their intended purposes, and for BDSM. While the physiological capacity to enter altered states of consciousness is available for lustful and spiritual purposes, and it is only in St Augustine’s wake that we take for granted they must be mutually exclusive, there is no clear boundary between spirituality and carnality that we do not draw for ourselves. The deadly seriousness of self-inflicted suffering in pursuit of a divine ideal is notably lacking in modern concepts of irony. Does that make any difference in how we know psychopathological behavior when we see it? I would be sorely tempted to diagnose religiously self-abusive behavior, despite the very considerable scaffolding of Western religious philosophy undergirding penance. The guiltier it was, and the less realistic I thought the guilt to be, the more I’d be inclined to diagnose a mental health condition. The doctrine of original sin just doesn’t persuade me that self-inflicted injury is a condign and effective response. The more I thought self-punishment led to ecstatic states, the less I’d be inclined to diagnose it. But that reflects a value judgment of mine that is not client-centered, which is another of my values.

The matter of the relevance of irony reflects a clinical observation of long standing, that clients with good senses of humor are generally more amenable to treatment than those without. And this observation makes sense to me clinically despite the countless examples in the consulting room when I have had to confront clients with interpretations that they were using humor defensively to distance themselves from the uncomfortable emotional significance of some clinical material. But somewhere in the upcoming Renaissance, we are going to exchange the fabulous demonic representations of Grunewald and the folksy humor of Breughel and Bosch for the insightful irony of Shakespeare, and the modern sensibility is marked by that distinction. In this way, Shakespeare is modern despite the archaic language and iambic pentameter. Hamlet means to discover the ‘real’ truth about the apparition he met on Elsinore’s battlements with a ‘fake’ play that reflects the alleged circumstances of his father’s death.

The test of a first rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function. F Scott Fitzgerald

Why humor is positively correlated with therapeutic outcome is, in part, a reflection of the clinical utility of being able to hold two feelings in mind at the same time and cross-ruff between them, creating a more nuanced appreciation of the problem under consideration. Apparently, it takes ambivalence to deconstruct ambivalence. Absolutists do not take readily to the kind of insight-oriented work that is the foundation of modern psychotherapy. I am inclined to view absolutism as a sign of intolerance of some feelings. And therefore I may be ready to put those who cling too tightly to The Great Chain of Being on the couch, which may well be indistinguishable to them from the rack. I wonder how many individual flagellants would have stopped following their cults if I interpreted their self-punishment as an attempt to control by displacement the frightening events in the chaotic world around them? Did the Holy Inquisition narrowly miss a golden opportunity to invent psychoanalysis 400 years early?

|

| The Pythons do the Inquisition. Not wholy unexpected! |

Lest one assume that modern notions of ambivalence and irony are a mere construction of Renaissance interest in internal human experience, it is worth looking at play. We define play as activity done for its own sake; that is inherently not utilitarian. A cat is playing with a ball of string, but we are inclined to think similar behavior with a mouse is predation, until the cat starts to show evidence of being more than single-mindedly devoted to killing it to eat. Tom and Jerry are not practicing their species-specific survival behaviors, they are just friends playing with each other. This example from the place where cartoon sadomasochism and ethology meet is intended to show that lots of behaviors are adaptive that do not immediately serve utilitarian functions. Cat’s play not because they are friends with the mouse, but because such behaviors have evolved to simultaneously serve long term evolutionary functions, and to provide short-term satisfactions. The adoption of a serious and non-ironic Medieval mindset was itself a social adaptation. There are plenty of tribal cultures with ironic wit, and the Dark ages were not dark because humor went entirely out of them.

|

| Tom and Jerry playing |

But the cat’s play, and the BDSM’s scene’s multi-layered use of the term ‘play’ have in common a kind of seriousness that goes beyond immediate gratification. In BDSM play, real wounds get inflicted, disobedience has real consequences, real body fluids get exchanged, and real a trauma can result from failed scenes and misunderstandings. Altered states of consciousness are only sometimes evoked. More often, people play in altered social states. In that sense, even with its ‘as-if’ qualities, BDSM play can be every bit as capable of discharging unconscious guilt as cold-blooded self-administration of a cilice. Play is serious, and seriousness may or may not be required for the enactment. This explains the chronicity of complaints about ‘smart-ass masochists.’ Despite a strong prevailing ideology in kink that masochists should be submissive, many are persistently provocative. They are playing with the seriousness of the scene and its ironic contexts, and tops struggle to decide how much control they surrender when they let masochists ‘top from the bottom’ by provoking them as a means of controlling their punishment it is the tops’ prerogative to mete out. Flagellants experienced a lack of agency, and were punished by the Church for trying to get more by illicit means. Smart-ass masochists are also blamed for trying to seize agency that is rightfully administered through intermediaries: tops! So are these situations analogous or different? What has changed so dramatically in 600 years is the language and voice we use to discuss and understand them. The play was always the thing, whether we recognized its seriousness or not at the time.

|

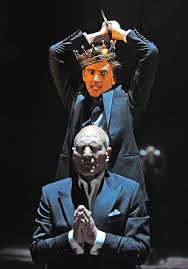

| Hamlet, Act III scene iii. Hamlet (David Tennant) considers killing the kneeling Claudius (Patrick Stewart) |

One final irony: In Hamlet, the strategy of the play-within-a-play is effective. Claudius freaks out and immediately rushes to his chapel to repent and pray. But Hamlet, brilliant as he may be, is a tragic hero, and his faith in empiricism betrays him. When he comes upon Claudius, seemingly in prayer, Hamlet’s direct observation misleads him. He assumes that Claudius is confessing and in repentance for his sins. But such is Hamlet’s hate that he will only be satisfied if Claudius is damned, and he dare not risk killing the vulnerable usurper if his soul might go to heaven, forgiven for his crimes. If Hamlet was a smart as we think he is, he’d have recalled from his studies that there can be no absolution for Claudius while he still has all the benefits he committed his murder to obtain. All would have ended in condign revenge if Hamlet had only trusted to his faith, not reason and direct observation, and killed Claudius while he had the chance!

“My Words fly up, my thoughts remain below,

Words without thoughts never, to Heaven, go.” Claudius

© Russell J Stambaugh, PhD, July 2013, Ann Arbor MI. All rights reserved.